February 4, 2024 by Anthony Randazzo, CFA

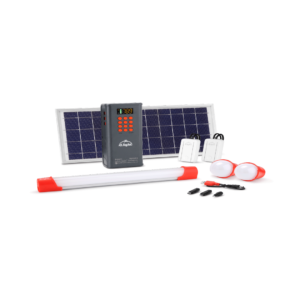

Around 700 million people living in developing countries, mostly in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, lack access to electricity, while several billion have either no power or only intermittent access from unstable, unreliable electricity grids. For these individuals, light and power comes from sources that are expensive, harmful, hazardous and polluting such as kerosene lamps and diesel generators. Founded in 2007, d.light is a for-profit social enterprise that designs, manufactures and distributes clean, affordable solar light and power products throughout the developing world. These “off-grid” solutions range from simple solar lanterns to solar home systems that can power several appliances, such as lights, cell phone chargers, fans, radios, refrigerators and TVs. The Impact Money Blog sat down with d.light’s co-founder, Nedjip Tozun, to learn about his journey as a social entrepreneur and to get his perspectives on the future of the off-grid solar sector.

d.light is a trailblazer in the off-grid solar market. It was one of the first to create products that displaced kerosene lamps with clean, solar powered lighting, as well as develop solar home systems. Looking back at your entrepreneurial journey, what would you say was the most challenging aspect of bringing a company like d.light to scale?

While several important technological advances were converging that made it a good time to launch a product to replace kerosene lamps, specifically lithium-ion batteries, solar panels and white LED lighting, I don’t think we realized how difficult it would be to commercialize and scale off-grid solar products. I spent the first 4 years at d.light living in China learning how to make the product with the right affordability and quality, while my business partner Sam Goldman was in India figuring out distribution and sales. We then expanded to Africa not long after that and quickly realized that to bring these solutions to scale we had to effectively build three distinct businesses.

First, was the business of producing durable, high-quality products designed for everyday use by people living in hard-to-reach, “off-grid” communities. That meant they had to be very affordable but also very durable. We had to take quality to a whole new level because in our markets the products have to operate in hot, dusty conditions and get dropped a lot. Your average camping store lighting would’ve failed within a week under the harsh conditions found in these villages. Getting the color of our product to exactly match our brand wasn’t important to our customers. It was about fine-tuning the requirements for our markets and working deeply with the entire supply chain to optimize the cost and quality that our customers needed.

While building great products started with solar lanterns, once our customers got access to lighting and realized what solar could do for them, they wanted more. So, we ended up building the whole “energy access ladder,” from super affordable entry-level solar lanterns all the way up to larger solar home systems that power appliances, including systems that could work where there is an unreliable and intermittent electricity grid.

So, we thought building a great product, at a great price that customers could afford and were willing to pay for was all that we needed to scale. But especially in emerging markets, the reality is there are no distribution partners with the scale you need. There’s no Walmart equivalent in rural Africa. So, the second business we needed to build was a direct to consumer (“B2C”) distribution business, which required building quite a bit of infrastructure with a different set of competencies and capabilities. Today we have tens of thousands of commission-based sales agents trained on how to sell solar. Alongside that is an after-sales network to repair and service products over time as well as support the installation of larger home systems. But all of that required a lot of investment and management time to bring it to scale.

With great products and distribution, we realized customers were ready to essentially leapfrog the electricity grid and gain energy access through these larger solar home systems that we brought to market. And they were affordable to the customers but only if the payments could be spread out over time. We had to enable them to pay daily or weekly at affordable rates to pay off the product over time, but the microfinance institutions and commercial banks just weren’t willing or able to finance the customers that were off-grid in Africa that we wanted to reach.

So, the third business we had to build was a pay-as-you-go financing company. As with distribution, we tried working with local partners first before doing it ourselves in-house, but ultimately, we realized we would hit a wall on how much we could scale. I’ve talked to a lot of entrepreneurs in emerging markets, and it’s a similar story. They end up having to build multiple lines of capabilities where in developed markets you could just work with various partners. This increases the risk and complexity of the business, but also creates defensive moats. It’s hard to manage all 3 businesses together, but if you can do it successfully, it makes it harder for new entrants. For example, mobile operators and big corporates (like Schneider Electric and Philips) tried to do solar financing and either stopped or pulled out. Others tried investing in companies similar to ours and pulled out. That speaks to the challenges, the complexities and the investment costs needed to get to where we are, which creates barriers to entry, but only if you survive.

What was your darkest moment along this journey?

There were a lot of ups and downs along the way where we frankly thought we weren’t going to make it, so it’s hard to single out one single darkest moment. I think the pivot to creating a distribution business was challenging because there are a lot of costs involved and we struggled to do that profitably. Once you build that distribution pipe, you have to have a lot of products to put through it with the right level of throughput. We knew it was a matter of life or death to get distribution right. The initial distribution partnerships had limited lifespans because it was hard in the early days. You had to educate the customer and build the category and after the initial honeymoon period there were just easier products for them to move. Building the distribution business required us to raise additional capital, and I remember that investment round when we thought we had secured the capital commitments, one investor pulled out, so we had to start over. My partner Sam and I didn’t pay ourselves for several months and we were running on fumes by the time we did close. But if we hadn’t closed, we wouldn’t be sitting here today.

In terms of other dark moments, the pivot to consumer finance was another. We could clearly see this was where the industry was going, which was crucial to bringing customers up the energy access ladder. We didn’t want to be a financing company, but the partnership that we had broke off, so we were either going to become irrelevant in the pay-as-you-go space or do it ourselves. But it was not a straightforward decision. We had to get our Board and investors on board, and there was a lot of internal debate. We had to raise another round of financing to scale up the consumer finance pivot and we were simultaneously running these pilots in Kenya that were do or die for the entire effort. But just in the nick of time, we managed to close the funding right as the pilots were staring to show some traction. I’ve talked to other companies in the same space with similar stories, some of which didn’t survive, not because they weren’t smart people or the businesses weren’t well-run, but because it is hard to do, and it takes grit. Luck and timing also play into it. Sometimes I feel like d.light has 9 lives.

We’ve seen some companies collapse over the years. Barefoot Power and Mobisol come to mind. Would you say the sector is following a classic evolution where you have early entrants, followed by rapid growth and competition, followed by consolidation, or is the evolution of this sector somehow unique? What stage of the evolution are we currently in?

Broadly speaking, we are seeing this trend, but with some nuances that make the picture look complex. There were a dozen or so companies that came up around the time we were founded, including Barefoot and Tough Stuff, that were essentially doing solar lanterns, but the ones that didn’t make the shift into consumer financing didn’t scale. And the solar lantern segment of the market became very commoditized. Chinese factories started making clones or similar products of lower quality, but were very cheap. So, it became a high volume, low margin business, and if you weren’t doing high volumes, you weren’t going to make any profit. Even with high volumes, you can’t really sustain your whole business on that because the margins are so thin. Whereas the lanterns were initially a core business for us, they later became more of a branding tool. We just got our brand out there and kept them low priced with a low margin and even outcompeted the Chinese factories. We did this because we realized that if someone’s first experience with solar is with you, and it’s a good one, where you’ve over delivered on your promises, then they are much more likely to stick with you as they make bigger investments into other higher margin products. So, players in that commoditized segment that weren’t able to shift or grow beyond that went under. Others failed for operational reasons, which is part of normal market consolidation.

Mobisol came in later. They raised huge amounts of capital and came in very fast, then had to figure out how to simultaneously build the product, the distribution and the consumer finance businesses, which is extremely challenging to do. There are also some successful companies that are local distribution and financing plays, where they source from us or another big player, but the reality is, in the bigger markets, it’s hard to compete unless you source directly and take a vertically integrated approach. Every successful company in this space operating in the bigger markets has been vertically integrated. For a company like d.light or Sun King that has been in this business for 15 years, it took us like five years to build each of the three businesses separately, starting with the product, then distribution then consumer finance. Each of which is hard, but at least we weren’t doing all three simultaneously, which is very challenging. There’s heightened operational complexity in this space. So, these companies that came in with large capital and tried to execute simultaneously on these three businesses really struggled.

Then with Covid and the supply chain bottlenecks and more recently the hyperinflation in some countries you’ve seen a lot of challenges facing the sector as a whole. Some companies are really struggling or suffering not because of natural consolidation forces but because they are in very difficult markets. For example, they are financing customers in currencies that have gone through hyperinflation, and this poses a particular challenge for companies with large amounts of US-dollar denominated debt on their balance sheet. In parallel to this, the equity market for our sector has largely dried up, not completely, but the exuberance of the sector has gone, and raising capital is more difficult. Interest rates are higher so that increases your cost of capital. We’re working in more erratic and vulnerable markets that are more prone to macro risks and shocks. Equity investors are more hesitant to deploy capital, which has caused a lot of companies to struggle with liquidity and scale. These macro events are having an impact and every company is feeling it. The social impact we have is immense and the potential to scale in the off-grid space is still massive, but if you operate in Nigeria, where the currency went from like 450 to 1,100 Naira to the U.S. dollar in a few months, and a large part of your balance sheet is in Naira but your debt and equity is in dollars, that’s really challenging to manage, even for large multinational corporations.

What has kept you going through these challenges and darkest moments?

It is several things. First, every time we visited customers in the field, we saw how our products were really transforming lives in a meaningful way. It wasn’t just “marketing speak.” Just by switching from a kerosene lamp to a solar lantern their life was so much better, and their kids could study at night. There was just an amazing transformation in their lives from such a simple product, so the impact we were having was immense. Just having that mission component to our work and knowing that what we were doing was really transforming lives, was really motivating for us to keep the engine going. This really felt like what I was meant to do and I just knew that I had to stick with it. I mean, even if the ship was going down, I was going to be the last person on the ship until it sank. I had that kind of mentality. When people see that on the team, they get inspired, and I got inspired by the team members who were having that same level of passion. It helps you ride through the storms. Having that sense of conviction and determination is important. We could see that with d.light it was really working and we just needed to weather the storm and get to the other side. That’s what kept me going.

Having the right sort of network around me, of people who support me, has also been really important to helping me navigate through. Having a good circle of friends outside of d.light that I could talk to and unload on was crucial. Also having great wife, as she’s been awesome and a great supporter.

I think of social entrepreneurs as being motivated by more than just making money. While they are classic entrepreneurs in that they solve problems that make our lives easier and get financially rewarded for doing so, social entrepreneurs are in my opinion different in that they are motivated to reduce poverty or to have a positive impact on the environment. Would you agree social entrepreneurs are fundamentally different and would you consider yourself a social entrepreneur?

I would agree that being a social entrepreneur is different. In the years leading up to founding d.light, I felt a real sense of calling towards social entrepreneurship. I think the difference is money wasn’t the main motivator for me. I had an offer with Google that I ended up rescinding once we got some funding for d.light. I could have made a lot more money going to Google, but that’s not what motivated me. When I started business school, my wife and I had just gotten married and the reason I was there was to start a social impact business, and there would be a financial trade-off in doing that. So the logic of starting d.light wasn’t “let’s make a lot of money.” It was “let’s impact a lot of lives,” let’s leverage this force of capitalism and entrepreneurship as a tool to really drive a lot of impact. If we make money along the way, that’s great, but that’s not really the main motivator.

I would agree that being a social entrepreneur is different. In the years leading up to founding d.light, I felt a real sense of calling towards social entrepreneurship. I think the difference is money wasn’t the main motivator for me. I had an offer with Google that I ended up rescinding once we got some funding for d.light. I could have made a lot more money going to Google, but that’s not what motivated me. When I started business school, my wife and I had just gotten married and the reason I was there was to start a social impact business, and there would be a financial trade-off in doing that. So the logic of starting d.light wasn’t “let’s make a lot of money.” It was “let’s impact a lot of lives,” let’s leverage this force of capitalism and entrepreneurship as a tool to really drive a lot of impact. If we make money along the way, that’s great, but that’s not really the main motivator.

Like I said, we had just gotten married, and I burdened us with a bunch of debt to go to business school, so I knew that money would be sort of a temptation, but because I came into it knowing what I wanted to do, we took some proactive steps and planned our finances so that money wouldn’t cloud our judgment. There were many things I could have done to maximize wealth, so my choices haven’t been governed by that.

In terms of the calling piece, it’s very tied to my own spiritual life. I’m a Christian, and I became a Christian in my mid-20s, which was surprising given my background because my mom is Jewish, my dad is Muslim and so I grew up with a lot of skepticism about organized religion. But my wife and I belong to a local church here, which has amazing people who are also doing great stuff in the world and are really motivated to make the world a better place and be a light into the world, both spiritually and concretely.

I also grew up knowing that where you were born could determine what opportunities you had, and this contrast was more extreme in other parts of the world. My personal gifts were entrepreneurship and technology and I really wanted to use those gifts to make a meaningful impact in the world. I was really attracted to what was happening at Stanford at that time, because they had this program called Design for Extreme Affordability. And I felt, oh man, this is exactly what I was meant to do. So much so that I only applied to Stanford thinking that if I got in, it was meant to be, if not, then not. But I did end up getting in. And there was about a dozen of us who were really interested in the whole idea of social entrepreneurship, and I was part of that Design for Extreme Affordability class my first year because I said if I go to Stanford, I have to do that my first year. I actually didn’t get into the class that first year, but I was so sure that that was the whole reason why I went to Stanford that I just kept showing up for that class for six or seven weeks and they finally let me in and that’s where d.light started out. So that was my personal journey, which felt like a calling and my purpose in business school. I wanted to leverage all the privileges I had access to to make a difference for people who didn’t have those opportunities.

I would like to explore the idea that there are trade-offs in becoming a social entrepreneur, because some founders of microfinance institutions who might be considered social entrepreneurs did quite well for themselves financially but faced criticism because of this idea that you shouldn’t make millions “off the backs of the poor.” Contrast that with the sub-prime mortgage crisis where greedy, unscrupulous people made millions selling home loans to people they knew couldn’t afford them and ended up wreaking havoc on the global financial system as a result. Shouldn’t we celebrate social entrepreneurs who build successful businesses that alleviate poverty and not denigrate that? Should there be this notion of sacrifice or trade-off if you decide to become a social entrepreneur?

If you are an entrepreneur and can scale something and deliver returns for investors, the founder and team should be rewarded financially for that. So, no, I don’t think it is bad if that outcome happens. That is great, and the fact is, when a company is at the point where it needs to attract commercial investors to scale to the next stage, that’s how that whole infrastructure works. Investors need to make their ROI and have high IRR requirements because of the risks, and if the investors achieve that return, I think that is good for the world, because it attracts more capital, and so the team and the founders should make their return. And I think that’s great. That’s part of tapping into capitalism, which is a powerful force. I think a lot of these founders are very mission-oriented, so even if they did make a lot of money, they are probably going to put it to good use.

But I would advise social entrepreneurs not to make that their main motivation. If that outcome happens, that is great. But for emerging markets, generally, while it is possible to make good financial returns, the odds are lower than in more traditional markets, and it will probably take a lot longer. These markets are generally higher risk and lower ROI, especially when trying to serve lower income customers. That is why initially we got a lot of impact investors around the table who provided patient capital to d.light. It is just very hard building those multiple businesses I mentioned. These things are not straightforward. So, for some businesses, it is not appropriate to have investors with high return requirements. Capital sources like that could help scale a business with a proven economic model but that kind of capital doesn’t apply to every kind of social enterprise. So, sometimes I find myself advising social entrepreneurs that their cause is very worthwhile, but expecting a high exit valuation or high return on investment is unrealistic because the market isn’t big enough, and maybe they should explore grants or other types of capital structures so that expectations aren’t misaligned. But if it is the appropriate time to tap into those commercial markets, then the commercial returns should apply to everyone, from investors to employees to founders.

What advice would you give to a social entrepreneur thinking to embark on a similar journey?

Take care of yourself for the long run because I’ve seen so many social entrepreneurs burn out. I nearly burned out a couple of times. So, I encourage entrepreneurs to figure out how to build a sustainable, balanced life so they can be in it for the long run. This means getting into a mindset that it is a marathon because as entrepreneurs, we can be constantly sprinting. There are certainly phases where you have to sprint, but you have to keep those phases time-bound in some way. You can’t always be sprinting. You need to have outlets that are going to fill you up and recharge your battery. There is the personal side, and the spiritual side, making sure those are cared for and having time with your family. I have a regular “date night” with my wife. It was important having dinner with the kids and carving out family time. Having friends and community are all really important for a sustainable life, long term. There are phases of life where you may have to hit it really hard for a couple of years, but those phases can’t go on indefinitely. d.light has been a 16-year journey, and it is still going. Entrepreneurs who want to have a social impact need to realize that it does take time.

Is there anything that you would have done differently in hindsight?

I definitely would have put in place more of those practices to prevent burnout in terms of time with my spouse and friends. On the business side there are probably one hundred things I would have done differently (laughs). I’m not even sure where I would start there. But seriously, I think it is all about the people and the team that you bring on board, especially as you get bigger. So, take time and care to make sure you bring on the right people with the right culture fit for your organization. It is something we do well now, but as you bring on more senior leaders, screening for values alignment is important. In the early days, we assumed that bringing someone with a lot of experience means they can fix issues, but it is not necessarily that simple, especially when you are pioneering and doing something new. Even if they have a lot of experience, they have to be flexible and be able to innovate and test new things and not be too set in their ways. Screening for that is something I would have done better in the early days. In hindsight, as the company scales, people who are great for a certain level of growth may not be for that next level. That applies even to myself. What makes you a successful leader getting from A to B won’t necessarily be what makes you successful getting from B to C. That requires having good feedback mechanisms, having coaching to realize your blind spots and hiring around those wherever possible, and then figuring out how to grow in other areas where you might be holding back the organization. Micromanagement can work just fine when you are a tiny startup but it is not a formula for success as a 100-person organization. You’ll drive everyone crazy and burn yourself out.

In terms of where this sector is going, looking at several companies in this space like M-Kopa, BBoxx, Sun King, SunCulture it seems they are pivoting in their business models. Some are selling phones and e-bikes and providing loans. Others describe themselves as fintechs or financing and distribution platforms. Where is this market going?

In some cases, you are seeing organizations pivoting away from product development and focusing on financing products in urban markets, which are easier to distribute to. But in other cases like d.light or BBoxx, we fit this category of having a wide range of products. d.light now finances phones and sells clean cookstoves. These are products that our customers want in their homes in their desire to leapfrog to having a modern household. We have never really been a solar company to them. First, we provided light and then we provided mobile phone charging, then fans and TVs. That is how they see us. The solar energy is just a means to that end for them. How the energy is produced is a secondary aspect.

In some cases, you are seeing organizations pivoting away from product development and focusing on financing products in urban markets, which are easier to distribute to. But in other cases like d.light or BBoxx, we fit this category of having a wide range of products. d.light now finances phones and sells clean cookstoves. These are products that our customers want in their homes in their desire to leapfrog to having a modern household. We have never really been a solar company to them. First, we provided light and then we provided mobile phone charging, then fans and TVs. That is how they see us. The solar energy is just a means to that end for them. How the energy is produced is a secondary aspect.

The product diversification is in part because customers are asking for this stuff, but from the business side, building distribution and consumer finance infrastructure is very expensive, so the more complementary products you can put through that distribution pipe, the better you can leverage that fixed cost investment to make it all work. This is why there is consolidation, because these companies are complex to run, they require a lot of fixed cost investment. If you are the number four or five player in the market, the volumes you are pumping through that distribution channel aren’t sufficient to be profitable. You have to have volume and volume is about market share. It is about having enough complementary products through that channel to enhance your customer’s life.

For us it is about providing off-grid customers everything that someone with a grid connection has. We want to provide all of that to them without needing to be plugged into the grid. But these customers cannot afford to buy appliances for cash, and what products are available might give them a horrible experience because they are not energy inefficient. But having a pay-as-you-go, energy-efficient TV, will give them a wonderful experience. It is the same logic for other appliances like fans or refrigerators. You are going to continue to see that trend. We have all this data on which customers are good payers, so we need a path to continue to enhance their life and upsell them and continue to engage them. Our customers have ambitions, and they want to continue upgrading their homes. So, I think there is a logic for companies in delivering that.

Given the macroeconomic backdrop, high interest rates, tight equity markets, what does your crystal ball say will happen next? Will there be more consolidation or more pivots? What is your prediction for where things are going for d.light and your competitors?

Unfortunately, I think some companies are going to go under. The companies that are struggling the most are the ones that are burning a lot of cash every month, and because equity is hard to raise it puts these companies in a very difficult position. There aren’t companies out there that can then absorb even more cash burn by acquiring other companies, so I don’t think we’ll see consolidation through acquisitions. There is going to be a real focus on generating operating cash flow and profitability rather than on maximizing growth, which will be healthy for the sector in the long run. I don’t really see a lot more equity flowing into this space in the near to medium term. I think companies really have to operate with that assumption, batten down the hatches and be sustainable. That said, I do think the business model is viable, there are some well-run companies. And we are starting to see the World Bank and others start to unlock significant capital for the off-grid sector that could really serve to open up new markets and drive growth for the companies that are well positioned to take advantage of it.

What would you say will be the next pivot, or would you say the focus will be on growing and selling more? Will there be further limits to penetration into rural areas? Where do you see the next inflection points as these companies mature and grow?

I think there is a business model that works now. There are so many companies that would have done really well last year if it weren’t for the currency madness and the interest rates. Thankfully, I don’t see a need to totally reinvent the business model or do something totally different or new.

There’s some saturation with the core solar home systems, for example, in Kenya, but then the customers want appliances. There is going to be room for continued growth from the demand side. I really don’t see that as being a constraint for the next 10 years because even homes that have solar system kits do not have refrigeration or TVs or water pumps. There are just so many other things these households want. Many have been paying 50 cents a day for their solar home systems and once they have paid that off, many will want to continue paying to have other assets in their homes. Many markets are under penetrated like Nigeria, Uganda and Tanzania. DRC is a huge market. So just executing on the current business model there is a lot to do, continuing to add new complementary product lines. That is not really a fundamental business model shift.

Are there other stories where you were surprised by or in awe of the impact you were having that you haven’t previously shared?

There are so many of those stories. I remember one family I visited had a young boy who was about my kid’s age at that time, four years old, who had serious asthma and breathing issues. He was always hacking, coughing and they had no idea it was because of the fumes emitted by their kerosene lamps. But once they got their solar home system, all of a sudden, the kid stopped coughing and was breathing normally and running around. I think just seeing that, especially with my kids being the same age, I mean, that had a powerful impact on me. You see with each of these families what the impact is. It really is transformational. Sometimes you see it show up in their health, or education as mentioned, sometimes it is the kids just being able to study longer, so their grades go up because they can read better at night. I remember talking with this woman who got a TV and she was so proud to be the woman in the village with the TV that people would come over to her house and watch. There was this dignity that the product gave her which was compelling.

How has your relationship with your co-founder Sam evolved over the last 16 years?

Sam and I have a very high trust relationship. We are pretty different people in a lot of ways, personality-wise, but very aligned in terms of our values. It is weird to say, but we have never really had a major disagreement. We certainly disagreed on things but mostly things like tactics. On the core issues we have always been aligned, which has been amazing. He and I have always had full trust in each other. When one person is in charge of something, the other provides support. It has been awesome working with him. It is great having a partner that you can confide in and talk to. I am so thankful that I have been on this journey with Sam over the years. The friendship has gotten deeper and trust has only increased over time. I do not take it for granted because I think it is really not the norm for a lot of people who start companies.

What does it take to be successful in this market, and what does it take to be a successful entrepreneur in this space?

I would say three things. One is perseverance. It is not easy and it takes time. Also, having a constant curiosity and willingness to test new things. What has worked for you in the past may not continue to work. Things can evolve in these markets so you might have to pivot. Having that sort of culture and mindset of let’s experiment, let’s try this and continually test new things and revisit things that may not have worked in the past and maybe can work now. Having a bit of that culture and process built in so you can capture the opportunities when they come up is important. Third, is having the right talent with the right values and alignment. To be able to have just a great team that can shoulder the load is important because it can be intense so you need really good people around who can help get the company to the next level.

What role do you think government and donors should play in supporting off grid solar in achieving SDG 7? What should they not do?

My thinking has sort of evolved on this. There is a “do no harm” aspect, where you do not want the government to come in and over-regulate or over-tax a new sector. And we want our solutions to be on a level playing field with kerosene lamps or diesel generators because a lot of times governments provide, for example, kerosene subsidies. I think there has been really good progress in leveling the playing field. Some kerosene subsidies have been rolled back and taxes have gone down for solar. That has helped level the playing field. Solar wins already from a cost-for-money and value-for-money perspective, so if the government just lets us compete and creates a free and fair market, solar is going to continue to grow. These products are going to be more and more affordable over time.

Energy is subsidized in a lot of places because there is so much benefit to society when people get energy access. In the early days of the industry, there were several subsidy programs that weren’t well designed and didn’t necessarily have the intended effect. But subsidy in the form of results-based financing for example, that the World Bank and other organizations have done in a couple of countries, is not about giving out grants indiscriminately. It is about proving you made a sale, in a hard-to-reach area of that country, for example. Those subsidies are great because they provide incentives by subsidizing the cost of companies to go into more difficult markets. As we get into markets like DRC, or if you want to get into harder areas in Kenya or Uganda or harder to reach parts of Nigeria, it is going to be important to have some level of subsidy to accelerate the process. Going in using commercially-raised dollars will be harder and take longer. So, there is a role for subsidy or concessionary capital to play there, and it is unlikely that money would come from local governments because they are typically cash strapped, especially now. Multilateral institutions could make a huge step change impact for these off-grid communities who will likely forever remain off grid. Assuming the right programs are put in place, these kinds of solutions will be the only way they will get energy access.